Posts

Fibonacci sequence in agile: why we use 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 for story points

Matt Lewandowski

Last updated 16/02/20268 min read

What the Fibonacci sequence actually is

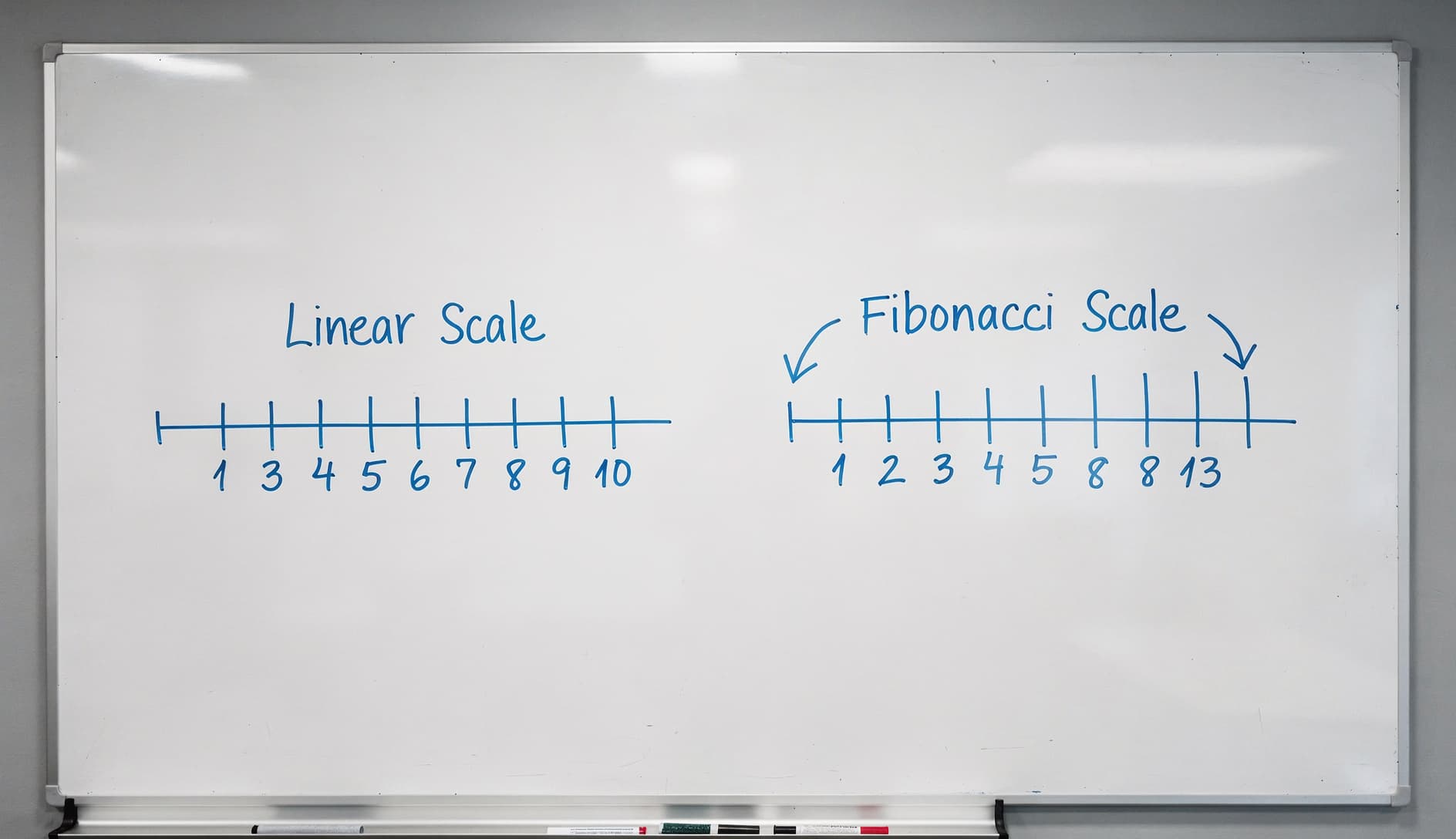

Why linear scales fail for estimation

Why the gaps matter

The cone of uncertainty

Forcing meaningful disagreement

Weber's Law

The modified Fibonacci sequence

The infinity and question mark cards