Posts

How to get actionable items out of your retrospectives

Matt Lewandowski

Last updated 16/02/202610 min read

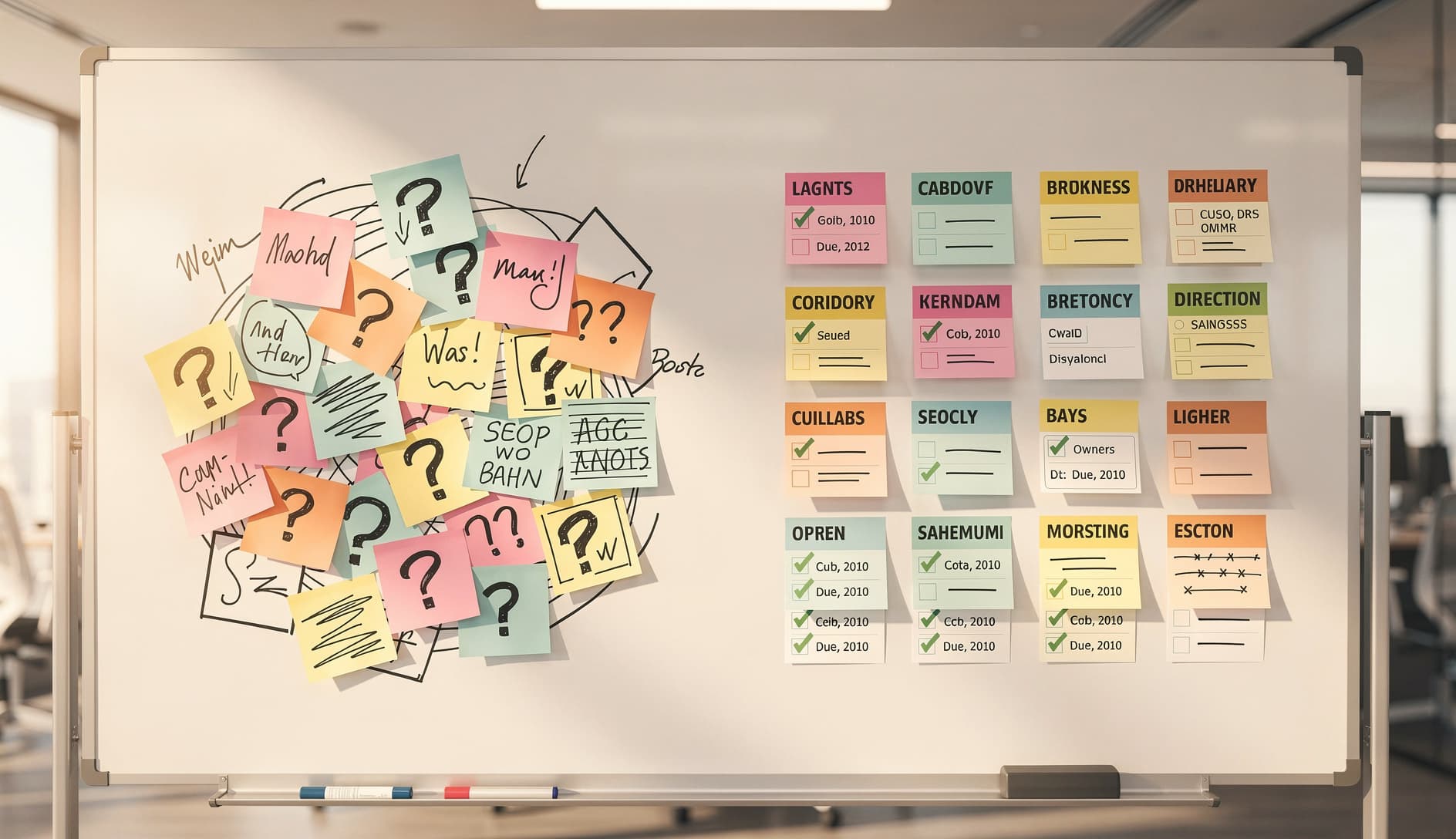

The action item graveyard

No owner

Too vague

Too ambitious

No tracking

What makes an action item actionable

Specific

Assigned

Time-bound

Measurable

Before and after: vague vs. actionable

| Vague action item | Actionable version |

|---|---|

| Improve code reviews | Add a 5-item checklist to the PR template by Wednesday, owned by Sarah |

| Communicate better about blockers | Post blockers in the #dev-blockers Slack channel within 1 hour of hitting them, starting this sprint, owned by the full team |

| Fix flaky tests | Identify and fix the top 3 flakiest tests in CI by end of sprint, owned by James |

| Plan better | Review the top 5 backlog items with the Product Owner before sprint planning on Tuesday, owned by Maria |

| Reduce meetings | Cancel the Wednesday sync and replace it with an async update in Slack for 2 sprints as an experiment, owned by Alex |

Techniques for generating better action items

Use the "who will do what by when" template

- Who is going to own this?

- What specifically are they going to do?

- When will it be done?

Vote on action items, not just problems

Limit to 1-3 action items per retro

Tracking follow-through

Review last sprint's items first